Introduction

Percutaneous lung biopsies are now the mainstay procedure in the evaluation of single or multiple lung lesions [1]. First introduced by Leyden [2] in the early 1880s, it was not until the 1970s that image-guided percutaneous lung biopsy gained general acceptance [3,4]. With the technical advances in computed tomography (CT) in recent years, CT is now the guidance modality of choice for performing percutaneous transthoracic needle biopsy (PTNB) [5]. It is currently recommended in cases where diagnosis cannot be obtained by endobronchial technique and when histopathological diagnosis will change the stage of disease or has therapeutic implications. CT-guided PTNB is a relatively safe procedure with limited morbidity and very low mortality [1,6-13] and diagnostic accuracy of more than 80% and 90% for benign and malignant lesions, respectively [1,6-11].

Pneumothorax and pulmonary haemorrhage are the most common complications of PTNB, with reported incidences of 8-64% [1,6-18] and 4-27% [19,20], respectively. Systemic air embolism, haemothorax, or pericardial tamponade are rarer but potentially fatal complications [12,21-24]. Other extremely rare complications include seeding of malignant cells into the needle track [25], lung torsion [26], and empyema [21]. Various studies have analysed the effect of various patient-related factors (e.g. age, sex, and emphysema) and lesion-related factors (e.g. site, size, and depth) on complications of CT-guided TNB; however, scant literature is available regarding procedure-related factors influencing the rate of complications. The purpose of our study was to analyse the influence of various patient-, lesion-, and procedure-related variables on the frequency of pneumothorax with special emphasis on procedural factors like patient position during the procedure, dwell time, and needle-pleural angle.

Material and methods

This was a prospective observational study conducted between September 2015 to October 2018 with approval from the Institutional Ethical Committee (IEC) and a sample size of 215. Prior to each procedure, the risks and benefits of PTNB were discussed with the patient and informed consent taken. Patients with focal chest lesions (nodule, mass, or a mass-like consolidation) and normal coagulation profiles, who could not be diagnosed by other modalities, were included in the study. Patients with severe emphysema, deranged coagulation profile, and haemodynamic instability were excluded from the study.

Diagnostic CT thorax was performed in all patients prior to the procedure. At the time of biopsy, which was done by an experienced radiologist, preliminary NCCT images of the thorax were obtained using a Siemens Somatom Sensation Open with scanning parameters of 120 kVp, 1.2 mm collimation, 40 mAs, and 5-mm slice thickness. The scan area was limited to the area just above and below the lesion to minimise radiation exposure. These images helped in planning the patient’s position, needle entry site, and direction of the needle. Care was taken to traverse the aerated lung as little as possible with avoidance of any bullae, fissures, and major vessels. Keeping the patient in prone, supine, lateral decubitus or oblique position, as per the lesion location, the biopsy was taken using a coaxial biopsy set comprising a 17- or 19-gauge outer introducer needle and corresponding 18- or 20-gauge cutting needle (Cook, Bloomington, Ind /Bard Peripheral Vascular, USA). The size of the coaxial biopsy set was chosen according to the size and depth of the lesion.

Under all aseptic precautions, local anaesthetic (10 ml of 1% lignocaine) was administered subcutaneously at the proposed puncture site. Under CT guidance, the introducer needle was placed into the extra-pleural soft tissues with needle-trajectory pointing towards the lesion. The needle was further advanced with path correction by intermittent CTs until we reached the surface of the lesion and penetrated it. A spring-loaded biopsy gun with cutting needle was manually introduced into the lesion and subsequently fired, retrieving a 2-cm tissue core. Two or three cores of tissue were obtained, which were immersed in 10% formalin and sent for histopathology. After removing the biopsy needle, post-procedure check CT was obtained with the patient in a supine position to detect any complications. Subsequently, patients were monitored in the parent department for at least three hours to detect any delayed complication. One and three hours posteroanterior (PA) chest X-rays were obtained before discharging the patient.

Image interpretation

Pneumothorax was measured as the maximum separation between the parietal and visceral pleural layers on CT and chest radiographs. It was quantified as small if ≤ 1 cm, medium if more than 1 cm but ≤ 3 cm, or large if > 3 cm or had a lateral component extending below the upper third of the thorax [27]. Multiple variables relating to the patient, lesion, and procedure were noted to determine the risk factors for the occurrence of pneumothorax. The patient variables included age, sex, and presence of pulmonary emphysema around the lesion on CT. The lesion-related factors were lobar location (upper, middle, or lower lobe), size (average of maximum diameter in two orthogonal planes), pleural contact, and lesion depth (amount of aerated lung traversed from the pleural surface to the lesion edge). Variables related to procedure were patient position during the procedure, needle gauge (18 G or 20 G), dwell time (time elapsed between pleural puncture and needle removal), and the needle-pleural angle (defined as the smaller angle between the trajectory of needle and the line drawn tangentially to the pleura at the puncture site). The needle-pleural angle was measured using an electronic calliper on axial 5-mm sections that documented placement of needle into the lesion most accurately (Figure 1).

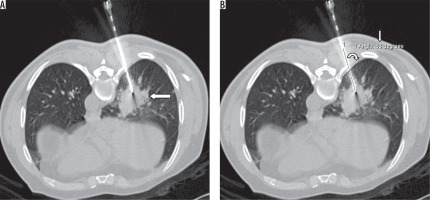

Figure 1

Axial NCCT image (A) obtained during PTNB in a 66-year-old male in prone position showing the needle in right lower lobe lung lesion (large arrow). Needle-pleural angle (curved arrow) of 63° (small arrow) measured using electronic callipers (B)

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed by a statistician using statistical software (SPSS, version 20.0). The various factors were compared between the two groups (with and without complications) using univariate analysis with two-sided Student’s t-test for numeric values and chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test for categoric values. To determine the independent risk factors for the occurrence of pneumothorax, the factors found to be statistically significant (p < 0.05) by univariate analysis were further subjected to multivariate analysis.

Results

In a total of 208 patients (male-to-female ratio 2.4 : 1), 215 lesions were sampled (seven patients were biopsied twice). A total of 215 biopsies were taken from chest lesions, of which 11 were mediastinal in location and approached through lung parenchyma. Mean age of patients was 59.4 years, with maximum number of patients biopsied in age range 61 to 70 years (35.3%). Pneumothorax occurred in 54 patients (25.12%). The various patient-related parameters and their relationship with occurrence of pneumothorax during the procedure are summarised in Table 1. Lesion and procedure-related factors and their relationship with post-procedural pneumothorax are shown in Table 2 and Table 3, respectively. Variables that were significant on univariate analysis (p < 0.005) were subjected to multivariate logistic regression analysis, and the results are summarised in Table 4.

Table 1

The relationship between patient-related parameters and occurrence of pneumothorax during the procedure

Table 2

The relationship between the lesion and the post-procedural pneumothorax

Table 3

The relationship between procedure-related factors and post-procedural pneumothorax

Discussion

Percutaneous transthoracic co-axial cutting needle biopsy of lung lesions was performed in 215 consecutive patients. Pneumothorax and pulmonary haemorrhage were the most common complications in our study, with post-procedural pneumothorax seen in 25.1% of patients (54 of 215 procedures), with chest tube placement required in 13% (seven of 54 pneumothorax cases). Findings were comparable to the rates observed by Charig et al. [28], Heyer et al. [29], and Chakrabarti et al. [30]. The difference between mean age of patients with and without post-procedural pneumothorax was statistically significant (p = 0.0020), implying that patients with advanced age had a greater chance of developing pneumothorax after percutaneous lung biopsy. The gender of the patient did not influence the pneumothorax rate in our study (p = 0.7761). No statistically significant relation was found between emphysema and frequency of pneumothorax in our study (p = 0.2724). However, patients with CT-documented emphysema developing pneumothorax required chest tube placement 10.9 times more frequently than patients without emphysema. The putative mechanism might be decreased pulmonary reserve leading to symptomatic pneumothorax in patients with emphysema. Disruption of emphysematous lung may also impede quick sealing of the air leak [13]. Emphysematous patients also have slow resorption of pneumothorax [8]. Our study thus showed no direct causal relationship of post-procedural pneumothorax with emphysema; however, it had a direct bearing on the chest-tube placement rate (Figure 2).

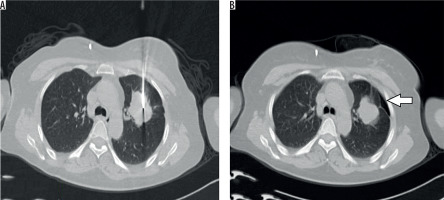

Figure 2

Axial NCCT image (A) obtained during PTNB of left parahilar mass in a 60-year-old male in prone position showing development of pneumothorax during the procedure. Background centriacinar emphysematous changes also noted. Post-procedural axial check NCCT image (B) obtained in supine position showing large left pneumothorax in the same patient. Three-hour post-procedural chest X-ray PA view (C) obtained in the same patient showing persistent left pneumothorax (arrow) necessitating chest tube placement

No significant correlation was found between lesion location and frequency of pneumothorax (p = 0.9320), which is comparable with the results of Cox et al. [14]. Lesion size correlated strongly with post-procedural pneumothorax rate (p = 0.0044), being 46.2% for lesions ≤ 3 cm and 22.2% for lesions > 3 cm. Cox et al. [14] and Yeow et al. [20] also reported strong correlation between lesion size and pneumothorax rate. The larger the lesion, the more its possibility of contacting the pleura, with less requirement of needle passage through the lung parenchyma. Another possible explanation may be less stable position of the needle tip in smaller lesions resulting in a to-and-fro motion during respiratory excursions, which in turn causes significant tearing of adjacent lung parenchyma, and hence pneumothorax. Superficial lesions contacting the pleural surface were seen in 51.2% of our cases, of which only 10% developed pneumothorax. For deeper lesions where the biopsy needle navigated through the aerated lung, the pneumothorax rate was approximately 43.3% (p ≤ 0.0001). The deeper the lesion, the more arduous it was to manipulate the needle into the lesion, implying multiple path corrections and greater tearing of the pleura (Figure 3).

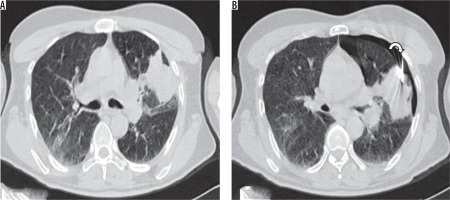

Figure 3

Axial NCCT image (A) obtained during PTNB in a 45-year-old patient showing co-axial needle in left upper lobe lung lesion. The needle is seen traversing the normal lung parenchyma. Post-procedural axial check NCCT image (B) in the same patient showing development of small pneumothorax (arrow)

No causal relation was seen between patient position and pneumothorax rate in our study (p = 0.9839). Similarly, there was no significant correlation (p = 0.7250) between pneumothorax rate and needle size (18 G vs. 20 G). However, there were many shortcomings with respect to the needle size and pneumothorax rate correlation. Firstly, there was no randomisation in selecting the needle gauge. There was a preferential bias in selecting the 20 G needle for smaller lesions (only 31 biopsies were performed with 20 G needle) and 18 G for larger lesions, and hence the effect of smaller lesion size, depth, needle path, and radiologist expertise might have biased our observation of statistically insignificant effect of needle size on pneumothorax rate. Cox et al. [14] and Yeow et al. [20] also demonstrated a lack of statistically significant difference in pneumothorax rates with the larger and the smaller gauge needles. Significant association was also seen between small needle-pleural angles (Figure 4) and pneumothorax rate (p = 0.0200). Higher frequency of pneumothorax was seen with needle-pleural angles < 70°. Ko et al. [27] and Hiraki et al. [31] also demonstrated significant association between small needle-pleural angles and pneumothorax rate. Needle insertion at an acute angle may result in stretching and tearing of pleura with a larger pleural hole in comparison to perpendicular needle insertion. A tiny pinhole can resist larger pressures, while a visible pleural tear buckles easily [32,33]. Lastly, no significant correlation was found between dwell time and pneumothorax rate (p = 0.9330), which is in resonance with the studies of Ko et al. [27] and Laurent et al. [16].

Figure 4

Axial NCCT image (A) in a 55-year-old patient showing a left upper lobe lung lesion abutting the costal pleura. B) Co-axial biopsy needle introduced at an acute angle (< 60°, curved arrow) with needle tip within the lesion. A small pneumothorax is seen during the procedure, probably due to introduction of the needle at an acute angle

In conclusion, our study demonstrated a significant effect of age of the patient, size and depth of the lesion, and needle-pleural angle on the incidence of post-procedural pneumothorax. Emphysema as such had no effect on pneumothorax rate, but once pneumothorax occurred, emphysematous patients were more likely to be symptomatic with delayed resorption of pneumothorax, thus necessitating chest tube placement. Gender of the patient, site of the lesion, patient position, and dwell time had no statistically significant relation with the frequency of post-procedural pneumothorax. Surprisingly, needle gauge had no significant effect on pneumothorax frequency, but due to the small sample size, non-randomisation, and bias in needle selection as per lesion size, further studies are required to fully elucidate the causal relationship between needle size and post-procedural pneumothorax rate.