Introduction

Epiploic appendagitis (EA), also known as appendicitis epiploicae, epiplopericolitis, or appendagitis, is a relatively rare, benign, and local inflammatory disease involving the epiploic appendices [1-4].

The epiploic appendices (or epiploic appendage or omental appendices) are peritoneal outpouchings generally located in two rows adjacent to the anterior and posterolateral taenia coli, characterised by adipose tissue, one or two arterioles that branch from the vasa recta longa of the colon, and a single draining venule [2,5-8]. Their role is not well known; it has been proposed that they can have a protective function towards intestinal vessels during the processes of distension or collapse of the colon [2,5].

These pedunculated omental fat protrusions have a normal thickness of 1-2 cm and a medium length of 3 cm (range between 5 mm and 5 cm), with the largest ones generally distributed adjacent to the sigmoid colon, and are located from the cecum to the recto-sigmoid in a number of 50-100 in most adults, not localising however near the rectum [9-13].

The term “epiploic appendagitis” was initially described in 1956 by Lynn et al., and its computed tomography (CT) features were described for the first time in 1986 by Danielson et al. [12,14-16].

This disease typically affects people aged 20-50 years, with a greater frequency in men than in women (4 : 1) [1,17-20].

Risk factors include male gender, obesity, intense exercise, colonic diverticula, and hernias [8,12]. EA can be primary or secondary. Primary EA is an inflammatory disease that may arise from a spontaneous torsion causing obstruction of blood flow within the omental appendage, then ischaemia up to a necrosis, or from spontaneous thrombosis of the draining vein and inflammation [13,15,21]. Instead, secondary EA may arise from adjacent inflammatory diseases involving the colonic wall and surrounding mesocolon, such as diverticulitis or appendicitis [1,12].

Thomas et al. reviewed 197 cases from the literature and 11 of their cases of EA, and classified each according to its cause: torsion and inflammation (73%), hernia incarceration (18%), intestinal obstruction (8%), and intraperitoneal loose body (1%) [12,22].

The most common sites involved by this disease are the rectosigmoid (57%) and the ileocecum (26%); rarer sites are the ascending (9%), transverse (6%), and descending colon (2%) [8,9,12]. Clinically, EA manifests in most cases (60-80%) with acute or subacute abdominal pain in the left lower quadrant, but it can also involve the right lower quadrant, thus miming other diseases such as appendicitis, diverticulitis, acute cholecystitis, and omental infarction [12,23,24]. However, most patients have a normal body temperature, and laboratory results generally show a normal white blood cell (WBC) count [12,25]. In fewer cases, patients also complain of diarrhoea and constipation [23].

Unlike its mimics, EA is a self-limiting inflammatory disease in most patients, with an average of 10 days, and can be treated conservatively, only with anti-inflammatory medication [1,3,11]; rarely it may cause the development of adhesion, bowel obstruction or intussusception, intraperitoneal loose body (peritoneal “mice”), peritonitis, and abscess [1,11]. For these reasons, it is very important to differentiate EA from the other diseases causing abdominal pain, such as acute appendicitis, which usually require surgery [1,8].

Today, ultrasound (US) and CT (preferred) scans play a crucial role in the diagnosis of this disease [12,26-28].

We present a rare case of epiploic appendagitis with the purpose of increasing awareness of this condition as a cause of acute-subacute abdominal pain and knowledge of its US and CT features, in order to avoid a diagnostic delay and unnecessary use of antibiotics, hospitalisation, and surgery.

Case presentation

A 33-year-old Caucasian male presented to our emergency department with a sever and sharp left iliac fossa pain that was sore on inspiration, coughing, and walking, which had started the day before. He denied nausea, vomiting, fever, alteration of intestinal habits, trauma to the area, dysuria, haematuria, loss of weight, or skin rash. Surgical history was negative and without chronic medications. Review of systems was otherwise negative. On abdominal examination he had localised tenderness in the left iliac fossa with guarding and rebound tenderness. There was no pulsatile or palpable mass, or costovertebral angle tenderness. Physical examination was otherwise unremarkable.

Therefore, the patient underwent laboratory and diagnostic tests. Laboratory results showed white blood cell (WBC) count of 14.10 × 1000/µl (4.8-10.8) with neutrophilia (88.6%).

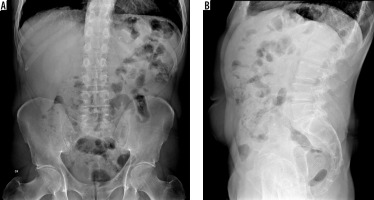

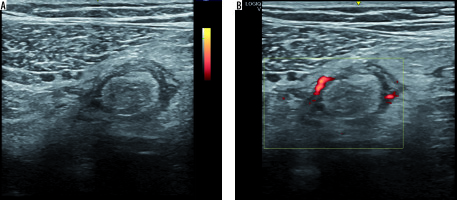

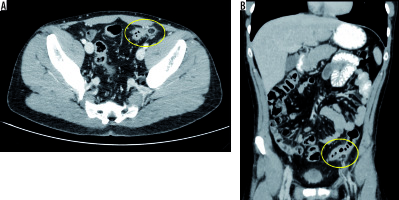

Abdominal X-ray showed no pathological air-fluid levels and no free subphrenic gas (Figure 1). An evaluation with abdominal US was performed and revealed a reactive bowel wall thickening of the descending and the sigmoid colon with inflammatory changes in the pericolonic fat, which appeared as an adjacent, oval, non-compressible, hyperechoic mass, without internal vascularity, surrounded by a subtle hypoechoic line and at least three perivisceral lymph node formations that were likely to be reactive (Figure 2). Abdominopelvic CT with intravenous and oral contrast agents was also performed and revealed a moderate reactive wall thickening of the descending and the sigmoid colon and a non-enhancing adjacent fat-density ovoid structure (16 ´ 18 ´ 15 mm) with high-density rim and surrounding inflammatory fat stranding (Figure 3).

Figure 2

Abdominal US image of the left lower quadrant showed a reactive bowel wall thickening of the descending and the sigmoid colon with inflammatory changes in the pericolonic fat, which appeared as an adjacent, oval, non-compressible, hyperechoic mass, without internal vascularity, surrounded by a subtle hypoechoic line, and at least three perivisceral lymph node formations that were likely to be reactive

Figure 3

Abdominopelvic computed tomography with intravenous and oral contrast agents (axial and coronal scans) showed a moderate reactive wall thickening of the descending and the sigmoid colon and a non-enhancing adjacent fat-density ovoid structure with high-density rim and surrounding inflammatory fat stranding

Discussion

EA is an uncommon cause of acute abdomen with a clinical presentation resembling other causes of acute abdominal pain such as diverticulitis and appendicitis. Indeed, before the widespread utilisation of modern diagnostic imaging techniques, in particular CT and US, the diagnosis of EA was usually made during surgical exploration while searching for unexplained cause of acute abdomen. Nowadays, although normal epiploic appendages are usually not evident in radiological studies, they result visible in inflammatory conditions and can be definitively diagnosed by contrast-enhanced CT (CECT) and US [3,29-31]. Moreover, other advanced imaging techniques can be useful in the diagnosis of this disease such as dual-energy CT (DECT), contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [20,32].

The classic CECT findings of acute EA consist of a well-defined, rounded or ovoid fat-attenuation mass abutting the wall of the colon, of 2 to 5 cm in size, enveloped by a continuous higher attenuation rim (the “hyperattenuating ring”) due to inflammation, which may occasionally involve the parietal peritoneum resulting in oedematous thickening appearances [3,7,33]. Acute EA can rarely cause thickening of the colonic wall or can be located in the hernia sac [34].

Another important CT feature, although not always visible, is the “central dot sign”, a central high attenuation region correlated to a thrombosed draining appendageal vessel or to internal haemorrhage or fibrous tissue [4,35,36]. An epiploic appendage may completely be separated from its pedicle, resulting in a wandering fatty abdominal mass that can calcify [7,12]. Other rare complications of EA include peritonitis, adhesions, abscess formation, bowel obstruction, and intussusception [37].

Additionally, in a recent study regarding the application of DECT for gastrointestinal imaging, it was highlighted that in the case of EA there is a higher iodine uptake of the surrounding fat secondary to inflammation, and lack of iodine uptake within the infarcted epiploic appendage [38]. The advantage of this technique is the full field of view and application of dose modulation in both acquisitions, as well as greater sensitivity than conventional CT alone without additional radiation dose for the patient [38].

The characteristic finding of acute EA on US is a hyperechoic, ovoid, non-compressible mass with a greater diameter ranging from 2 to 4 cm. The lesion is located at the site of maximum tenderness, usually under the abdominal wall, and is attached to the adjacent colonic wall. Moreover, it may show a peripherical hypoechoic rim due to thickening of the serosal covering of appendages and of the parietal peritoneum [7,12]. In colour Doppler US, acute EA shows absent or weak internal blood flow, in contrast to appendicitis or diverticulitis, which are abundantly vascularised [12]. The use of CEUS may be useful to confirm the diagnosis of EA in unclear cases. On CEUS, lesions show a central area of no enhancement with a variable thickness of perilesional enhancement (> 1 cm in most cases) [39].

Although magnetic resonance is not routinely performed, MRI findings of epiploic appendagitis appear to correlate with CT findings. In this regard, T1- and T2-weighted images show a focal lesion with the signal intensity of fat and a peripherical enhancing rim on post-gadolinium T1-weighted images [40].

CECT imaging surely represent the method of choice to detect EA and exclude other acute abdominal diseases that which are considered in the differential diagnosis, such as acute appendicitis, acute diverticulitis, acute omental infarction, sclerosing mesenteritis, and tumour or metastasis to the mesocolon. For females, it is important to take into account also ovarian torsion, ovarian cyst rupture, and ectopic pregnancy [3].

Conclusions

Unlike its mimics, EA is a self-limiting inflammatory condition and generally requires conservative treatment [3,7,12,20]. For these reasons, radiologists’ knowledge and awareness of EA as a cause for abdominal pain and its radiographic findings can prevent unnecessary hospitalisation and surgery [1,7].